The banjo player looks back on his beginnings with Jacken Elswyth

Every day, for almost 10 years now, I've been receiving alerts sent to my email inbox by Google, programmed to send me "only the best results" of content including the keyword "fugue" listed by the search engine.

At the time, I had the idea of creating my own magazine, the first issue of which would have had "the road" as its theme.

Although my initial intention was to observe fugues, the polysemy of the term means that I end up with around 40% of content concerning the fugue as a musical motif.

This haphazard aggregation of data from two different fields - social behavior and musical form - provided me with some interesting ideas for my magazine. I would have been well advised to take an interest in folk music and its history, intrinsically linked to the migrations of the people and instruments that gave it life. Although the magazine project never saw the light of day, I still had a kink for emancipatory approaches, misunderstood teenagers, Gregg Araki films and hitchhiking.

And this winter, I've been obsessed, or at least fascinated, by the music of trans/queer/communist artist Jacken Elswyth, who performs a technical back-and-forth between Gaelic tunes, American folk ballads, improvisations and musique concrète on banjos she restores or makes herself. But this compact description does not do justice to, or even opposes, the feeling of linearity, minimal, melodic and constant that her music constantly renews. Thanks to this line, it's easy to take off, because it's taut.

On YoutubeThe videos posted by the London-based musician feature melodies that seem to repeat themselves without being unambiguous. With her right hand bent, she alternates bounces of the index and middle fingers with beats of the thumb on the first string, played empty. This drone string, which always produces the same note (that of the key in which the banjo is tuned, often G), is like a unifying thread. A percussive technique, characteristic of the "old-time" style, it enables us to follow the rhythm, even without being initiated. It's a bit like entering a Breton dance circle where all the participants are holding on to each other's little finger.

Except that, unlike the frozen representation of this dance in time, Jacken Elswyth's music seems to open up our listening. In his interpretation of " Red Prairie Dawn With the new "Fretless Banjo", shifts from one note to another are effortless and destabilizing. The fretless banjo she uses lends itself particularly well to these glides, which offer flexibility in playing. In the comments, she replies to a user who asks about the technique: " My best advice would be not to over-tighten and slip in the notes, and not to worry if it's a bit fuzzy*! ".

While it's true that today's musicians can learn folk music from Spotify or Youtube, the early imagination is characterized by oral transmission, which is at the origin of the circulation of melodies and a plurality of versions.

Except that when searching on Youtube, I often get the impression of being taken for a tourist. While some of the artists' mastery of medieval instruments or their voices, which seem to converse with those of angels, are awe-inspiring, there's a sense of tradition that's impervious to contemporary influences.

From the very first seconds of " Princess Royal With Jacken Elswyth's "Unpacking of Folk", it's understood that I'm not going to attend an "unpacking of folk" in costume and filmed in front of a green screen to be replaced by a porch or a waterfall.

In her solo albums and with the improvisational folk group Shovel Dance Collective, Jacken Elswyth seems to rise above performance to convey only the essence of song and sound.

To quote Andy Cush in a article published in 2023 on Pitchfork about Shovel Dance Collective's latest album: " The London-based collective approaches folk song as a living tradition, not as a museum piece*."

Similarly, Jacken Elswyth emphasizes simplicity in his banjo-making:

" I'm not looking to do a historical reconstruction, but to produce instruments that fit into a clear lineage of folk craftsmanship. While I hope to make beautiful instruments, I find that their beauty lies largely in the simplicity of the techniques and materials used in their construction*." she explains on her website.

With its series of cassettes, Betwitx & Betweenbegun in 2018, Elswyth is breaking new ground in the genre. A combination of her work and that of other artists in the same vein, she combines contemporary improvisational techniques and interpretations with traditional songs of English, Irish or American origin, dating back as far as the last three centuries. You'll appreciate the diversity of sound and music, with its mix of enveloping drones, metallic rock stamps and ceremonial shruti-box.

In preparation for writing this article, I'm chatting with two friends who play in a folk band, and we get to talking about oral transmission. They tell me that while for some, oral transmission is a guarantee of authenticity, the authenticity of folk music is in any case conducive to pre-fabrication.

On the website of the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, the online archive founded by English folk music collector Cecil Sharp and featuring the UK's largest collection of songs, dances and traditional music, you'll find over 200 versions of "The Elfin Knight", a melody that could date as far back as the 12th century, and is said to have served as material for Simon & Garfunkel's "Scarborough Fair".

This open-source availability suggests the idea of openness and a certain fidelity in the collection process.

However, a little digging turns up the diaries of Cecil Sharp and his secretary, who set out to record songs of English or Irish origin in the Appalachian mountains of the USA in the early 20th century. The idea was to bring them back, as they would have been imported and passed on by emigrants from the British Isles. The impressions they conveyed in their journals reveal deeply racist practices, denying any interest in stopping at places where they encountered African-Americans, themselves the originators of the banjo's importation during the slave trade. Indeed, the authenticity of folk music seems to be an obsolete issue.

In a recent interview on the Rewire FestivalShovel Dance Collective points to this denial of origins in favor of a movement driven by archivists and researchers to bring back authentic English folk culture.

According to the group: " Early English collectors, such as Cecil Sharp, were driven by the quest for an authentically "English" culture, omitting songs that didn't fit their ideal. Often, they purged lyrics that were too sexual, crude or rebellious. Sharp and others also fostered a process of racialization that erased the international and geographically fluid nature of folk song, particularly in their racist denial of the black origins of "English" shanties*.. "

With their album The Water Is the Shovel of The Shore which mixes religious songs, field recordings and traditional instruments, they revive these shanties (seafarers' songs from the 18th or 19th century) and rejuvenate the idea of taking an interest in traditions that are in the process of disappearing.

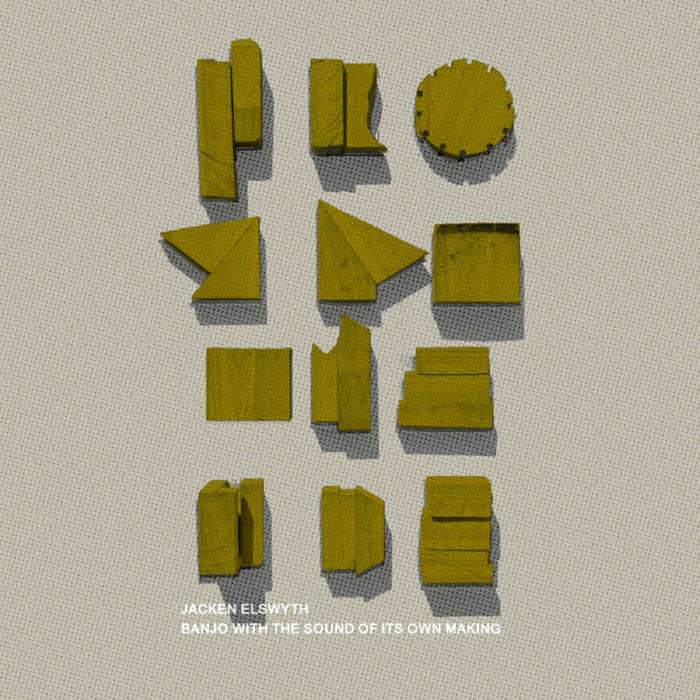

Of Elswyth's work, the album " Banjo with the Sound of its own making "The banjo-making process is integrated, in the form of field recordings, and broadcast in shuffle mode alongside the rest.

Defying all chronology, the album allows us to hear the sound played by the banjo, while it is technically in progress. The connection to experimental and improvised music honors the cross-pollination intrinsic to folk.

Sartre said something like "we can always make something of what we've made of ourselves", and somehow Elswyth's approach seems to tell us that everything is already in our hands to access an energy in the present, while honoring the past. " Stringless, gut-strung and made from readily available materials, the mountain banjo was a return to basics for people who couldn't afford to buy one.*" she explains on her website.

Alan Lomax's innumerable collections to explore via his archives online, also invites us to revisit field recordings. Interested in the "raw" material of folk and its diversity, Lomax was the first to record and introduce black and white musicians who became popular blues and folk figures such as Muddy Waters and Bessie Jones.

The podcast " Been all around this world "Recently released by the Alan Lomax Archive Youtube channel, these episodes delve into the recordings he made from the 1930s to the early 1990s. Presented thematically and narrated by Nathan Salsburg, the episodes look at aspects (instrumentalists), places (Texas) or specific moments (lullabies) of folk history, and bring out something as fluid and moving as the human experience.

Thanks to Chris Sergeant and Guy for their valuable contribution to this article.

*I translate.