Reviving folk energy with Jacken Elswyth

Every day, for almost 10 years now, I've been receiving alerts sent to my e-mail inbox by Google, programmed to send me the top results for content including the keyword "runaway". This rather pointless process has never really served any purpose, apart from cluttering up my e-mail inbox and fostering a kink for emancipatory approaches, misunderstood teenagers, Gregg Araki films and freight train riders.

Last winter, I added to my collection of "rebellious musings" the music of Jacken Elswyth, who, against all odds, performs a technical back-and-forth between Gaelic tunes, American folk ballads, improvisations and musique concrète on banjos she restores or makes herself.

Here, emancipation is not a matter of angry refrains or perilous soundscapes, but of elegant expression that seems constantly renewed from the very essence of the banjo, from which emerges a sensation of linearity, minimal and sufficient.

On Youtube, the London-based musician sits on the bed in her bedroom or studio. The decor is simple, highlighting natural materials such as wood, or nature when she films herself in a garden. The melodies she plays seem to repeat themselves without being unambiguous. With her right hand bent, in the clawhammer technique, she alternates bounces of the index and middle fingers with beats of the thumb on the first string, played empty. This drone string, which always produces the same note (that of the key in which the banjo is tuned), is like a unifying thread. A percussive technique, characteristic of the old-time style, it enables us to follow the rhythm, even without being initiated. It's a bit like entering a Breton dance circle where all the participants are holding on to each other's little finger.

In her interpretation of "Red Prairie Dawn", the shifts from one note to another are effortless and destabilizing. In the comments, she responds to a user who asks about technique with a fretless banjo, i.e. where the neck is not delimited by a grid of notes: "My best advice would be not to over-tighten and slide into the notes, and not to worry if it's a bit fuzzy!".

With its series of cassettes, Betwitx & Betweenbegun in 2018, Elswyth combines her work with that of other artists in the same vein. She combines contemporary improvisational techniques and interpretations with traditional songs of English, Irish or American origin, dating back as far as the last three centuries. You'll appreciate the diversity of sound and music, with its mix of enveloping drones, metallic rock timbres and ceremonial shruti-box.

Today's folk musicians can find plenty of material on Spotify or Youtube, but the early folk imaginary is characterized by oral transmission, which is the source of the circulation of melodies and a plurality of versions.

On the website of the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, the online archive founded by English folk music collector Cecil Sharp and featuring the UK's largest collection of songs, dances and traditional music, you'll find over 200 versions of "The Elfin Knight", a melody that could date as far back as the 12th century, and is said to have served as material for "Scarborough Fair", also performed by Simon & Garfunkel.

Folk music has always been somewhat cover-based, and the gap between the age of the original material and that of recent versions on Youtube more often than not gives rise to the embarrassing sensation of being a tourist at Disneyland. I don't want to criticize the mastery of medieval instruments or the voices that manage to converse with angels, but it's clear that I'm not going to be moved by an unpacking of folk filmed in front of a porch or a waterfall.

In solo performances or with the improvisation group Shovel Dance CollectiveJacken Elswyth seems to rise above performance to convey only the essence of the songs and sounds. With no set, no frets, all you get is what passes through the instrument.

In preparation for writing this article, I'm chatting with two friends who play in a folk band, and we get to talking about oral transmission. They tell me that while for some, oral transmission is a guarantee of authenticity, the authenticity of folk music is in any case conducive to pre-fabrication.

In a interview on the Rewire Festival website, Shovel Dance Collective points to this denial of origins in favor of a movement to bring back authentic English folk culture, led by archivists and researchers.

According to the group: "Early English collectors, such as Cecil Sharp, were driven by the quest for an authentically 'English' culture, omitting songs that didn't fit their ideal. Often, they purged lyrics that were too sexual, crude or rebellious. Sharp and others also fostered a process of racialization that erased the international and geographically fluid nature of folk song, particularly in their racist denial of the black origins of the "English" shanties.

With their album The Water Is the Shovel of The Shore which blends religious songs, field recordings and traditional instruments, they revive these shanties (seafaring songs from the 18th and 19th centuries).

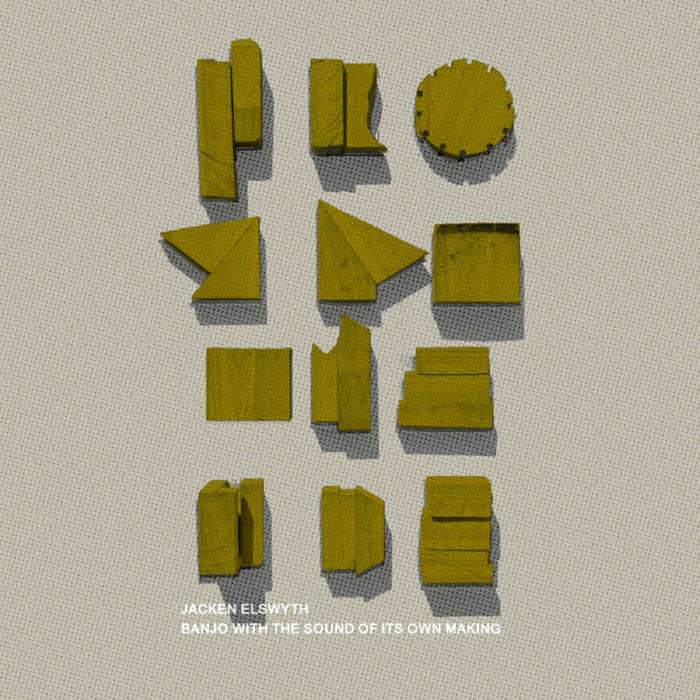

One of my favorite Jacken Elswyth listening sessions was the album "Banjo with the Sound of its own making" on a particularly cold Berlin winter's day. Defying all chronology, the album allows us to hear the sound played by the banjo as it is technically being made. The sound of the banjo being made integrates my living room, I hear field recordings of wood, played in shuffle mode alongside the rest. I'm bathed in the scent of pad-thai and Ingwer Tee. How nice, I tell myself.

Sartre said something like "you can always make something of what you've made of yourself", and somehow Elswyth's approach seems to tell us that everything is already in our hands to access energy in the present.

Thanks to Chris Sergeant and Guy for their valuable contribution to this article.